Color is a tricky thing. It seems so self-evident, so objective, so out there. It’s something we see, something we smell, something we even seem to taste. And yet color as we know it is also a function of our eyeballs, a pairing of lenses and receptors as unique to ourselves as is our own DNA or our own life stories. Most of us have receptors that distinguish three colors (red, green, and blue), some have only two, while others see only darkness or light, and still others have additional receptors that sense a fourth color somewhere in the yellow range. So if color is a property that depends not only on the things that we see but also on the people who see them, then how do we study colors in the past?

Viking Age Glass Trade Beads

This is an important problem for me, as I study the trade routes of northern Europe at the dawn of the Viking Age (ca. 700–900 AD). This was a period in which long-distance exchange functioned without a coin economy, and yet certain commodities seem to have been exchanged regularly as if they were cash. Later on, this included hacked up bits of precious metal, especially silver, which helped lead to the coin economies of the later Middle Ages. But during the early period that I study, the long-distance exchange item that seems to have been used in every market, on every farm, and in every cemetery was glass beads. They are our keys to understanding the trade routes of northern Europe in an era before minted coins and written trade records.

Viking Age Scandinavians traded far and wide for beads of colorful glass and semiprecious stone, and they buried them in their graves and in their hoards. These glass beads come from one of northern Europe’s richest early medieval cemeteries at Smorrenge on Bornholm. (Photo: Author. Bornholms Museum, Rønne, Denmark.)

Classifying Ancient Beads

Modern scholars have defined a number of systems for describing and classifying early medieval beads. Without exception, they have relied on color as a primary characteristic. Certainly, color is one of the most important properties of these ancient beads. Early medieval glass tends to fall within narrow ranges of blue, green, yellow, red, orange, and white. Glassmakers achieved these colors through a fairly consistent use of additive chemicals. But neither they nor their consumers would have sensed these colors in exactly the same ways, nor do the scholars examining these artifacts today. The problem is compounded by the fact that bead makers and bead consumers might have spoken different languages or dialects during the Viking Age, and that these are all necessarily different from the array of languages used by bead researchers today. Each person describes color with their own vocabulary, which they tack onto their own individual experiences of color.

This badly beaten bead retains clay from its manufacture along the inside perforation, and its outside has been corroded by the soil and damaged by the plow. But the fragile bead was broken sometime after excavation, revealing the original color of the brilliant blue glass and allowing comparison with its damaged and graying surfaces. (Photo: Author. Bornholms Museum, Rønne, Bornholm.)

Munsell Bead Color Book Provides a Universal Color Reference

There is no easy method for navigating these problems, but the Munsell Color System helps. International use of the Munsell Soil Color Chart has prepared researchers for its use in other areas as well, and the Munsell Bead Color Book has already proven its worth as the standard reference for U.S. archaeologists studying beads. By offering a standard reference point, the Munsell system can help an international group of bead researchers to discriminate such things as red beads from beads that belong to the neighboring colors of orange, purple, black, white, or gray—without having to worry about the ambiguities that their own subjective perceptions of color or uses of language can introduce.

The Munsell system not only provides a universal color reference for researchers; it also allows them to observe aspects of color that people of the past might have thought were more significant than we do today. We often think about colors in terms of reproducing them in the hues of red, green, and blue used by our TVs, or in the hues of cyan, magenta, and yellow used by our copiers and printers. In contrast, a viking might navigate dangerous waters by following the intensity of the deep blue sea, and a farmer might ration precious winter feed by judging the sheen of an animal’s coat. The Munsell system moves beyond our modern interest in hue to include these alternative interests in intensity and brightness. Researchers using the Munsell system measure not just a color’s hue but also its value (how much white or black it includes) and its chroma (its purity or the inclusion of other colors). Scholars of the early Middle Ages have already found evidence that these aspects of color could be more important than hue in early Western European art and writing. The Munsell system provides a way for testing whether intensity and brightness carried similar significance among the Scandinavians of the Viking Age.

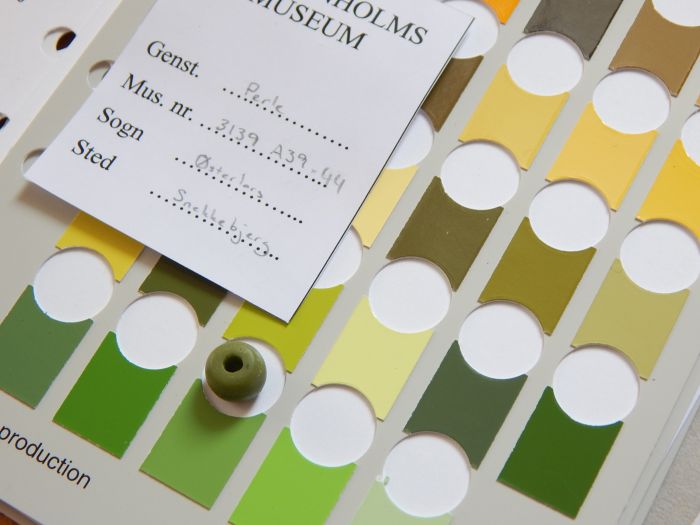

Not all ancient beads perfectly match the color chips selected for the Munsell Bead Color Book, but exceptions are rare and can easily be recorded. The Munsell system introduces a new degree of precision to early medieval bead studies, with the potential to tell us more not just about how people perceived and used beads, but also about how they interacted with the wider world around them. (Photo: Author. Bornholms Museum, Rønne, Denmark.)

The Munsell system does, of course, have its limitations. Different observers working under different conditions may record different colors for the same bead. These ancient beads have often suffered wear and corrosion from a thousand years lying in the soil and under the plough, which can significantly impact the colors on their surface. And although my initial sampling of Viking Age glass beads has shown that most can be matched to one of the 176 color chips included in the Munsell Bead Color Book, some beads have no matching color, particularly those within the yellow–green range.

Despite these objections, scholars have long used color as a basic characteristic for sorting and classifying Viking Age glass beads, and the Munsell system offers them greater precision for doing just that. By correlating the colors visible on the worn exteriors to those appearing along fresh fractures due to modern excavations or rough handling, we can measure just how far modern observations deviate from the beads’ original appearance. And finally, by comparing the beads’ Munsell colors to other data such as their shapes, sizes, and decorations, we can assess how closely the colors that we see correspond to how Viking Age beadmakers organized the colors of their craft, giving us greater insight into how these colors, and the trade beads that carried them, moved across the Viking World.

About Matthew Delvaux

Matthew Delvaux is a doctoral candidate studying the slave trade of the Viking Age. He currently works in the History Department at Boston College and has previously completed an MA in history at the University of Florida and a BS in history and foreign languages at the United States Military Academy at West Point. His archaeological experience includes field and laboratory work in Florida, Massachusetts, Denmark, and Sweden. You can read more about his research on his personal blog or follow his professional endeavors on Academia.edu or LinkedIn.

nice article

Have you looked at the color system used by gemologists? Find a AGS (American Gemological Society) member in your locality. Also using high gravity liquids and fiber optic lighting allows one to look at the inside of a stone (or glass) without the surface interference, in gemology this is used for rough stones, but could work well with damage or wear on glass. The GIA sells HG liquids. (Gemological Institute of America, GIA.EDU). You might be surprised at what a worn bead will look like in the right HG liquid !

I’m a glass beadmaker, and I’m looking at viking beads, with a view to recreating some of the patterns. I would definitely look at the colours of modern beadmakers’ glass rods, as the same minerals and metals are used to achieve their colouration. I’d love to know which minerals the Vikings used in their beads. With that knowledge, I’d know exactly which modern glass colours to choose.