That scarf you bought at one store that matches a hat you bought at another is not a coincidence. For decades, color professionals have influenced the colors that are produced and promoted. In The Color Revolution, historian Regina Lee Blaszczyk takes us on a journey, sharing the innovators stories and the beginnings of color forecasting and trends.

Can you explain what you mean by “Color Revolution?”

The term “color revolution” comes from an article that was published in the very first issue of Fortune magazine in February 1930. In this article, called Color in Industry, the editors of Fortune magazine looked around them and said, my goodness, so much has changed in the material world since World War I. We have pots and pans that are bright green, we have fabrics that are bright purple, we have cars and appliances that are multi-colored. . . . There has been a color revolution going on in America over the past decade. So the term “color revolution” comes from Fortune magazine. The book looks at the color revolution that emerged in the 1920’s but had roots going back to the 19th century and that evolved moving forward into the 1930’s, 40’s, 50’s and 60’s.

Your book shares many stories about color throughout, which is your favorite?

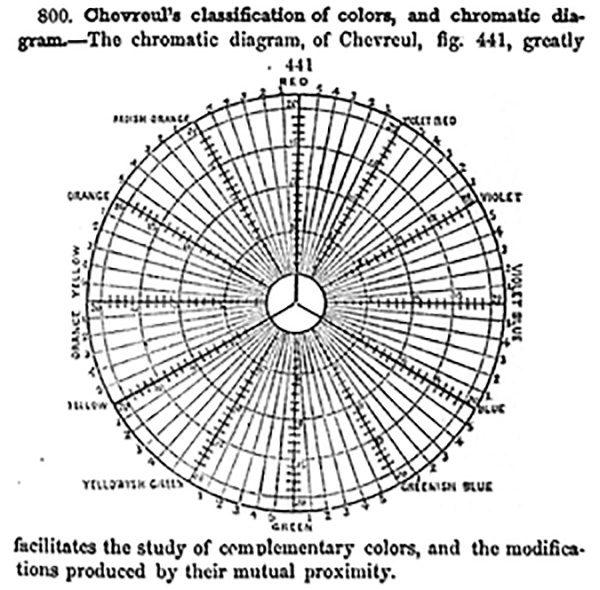

Of course one of my favorite stories is about Albert Munsell. Munsell is one of the important color-related inventors who operated in the period from 1890 to 1918. He is critical to the book because he is a prelude to the full-blown color revolution that came about after his death. He is interesting in that he was an artist and an intellectual omnivore as well. He was an art teacher at what is now the Massachusetts College of Art in Boston. He had studied in France and visited the tapestry works where Michel-Eugene Chevreul was still working as a very old man in the 1880’s. He became fascinated with the problem of how to use color in his own artwork and more specifically about how to teach color. He spent a good two decades developing nomenclature systems for describing color and tools for teaching color in the classroom.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

What is it about Munsell that drew you to him?

I think that Munsell is interesting to me because he’s so human. When you read the transcript of his diary, his struggles as an entrepreneur really come out. He struggles to move from being an artist to an entrepreneur. You see people visiting his studio–all of these scientists from MIT come to talk to him about color psychology and the physics of color. He’s networking with people at Harvard. He’s really frustrated when he enters the business world because he can’t get a grip on that angle. What’s intriguing about the way the story unfolds from his diary is that is shows that he’s not a hero, he was actually a very human person that was struggling. Of course the critique of his work on color by others in Massachusetts shows the reality of what it’s like to be an inventor operating in this slippery world know as color.

How successful was Munsell during his lifetime?

He was a very ambitious guy, but his ambitions where somewhat thwarted by the fact that he was inventing his color system at the moment when Milton Bradley and Louis Prang, two prominent printers in Massachusetts, had cornered the market for art supplies. So although Munsell developed an atlas of color charts, invented a color sphere and invented a whole host of other color teaching materials, he was somewhat limited in his ability to move from inventor to innovator.

Munsell struggled in securing a printer [chromolithographer], who could reproduce the color accurately in his color chart. Although his system was innovative at the time, he had difficulties taking it to market. The book makes the point with Munsell that you can have a great idea or invention, but unless you have the means to take it to market, your invention may not prove to be as profitable as it could be. This is the challenge many of color revolutionaries faced as the story moves forward in time.

How did the competition between Munsell and the color theorists Bradley and Prang effect Munsell’s research?

I think that Munsell was preoccupied with the competition from Milton Bradley and Louis Prang, and like all innovators, he was challenged by his rivals. Munsell was not the first to invent a color system. Bradley and Prang were two important businessmen in Massachusetts; each ran a high-profile chromolithography business and, in the late 1800’s, introduced color systems. Bradley and Prang were art supply manufactures so they had somewhat of an “in” with the Massachusetts board of education. They had convinced the board of education to include color lessons in the state curriculum.

It’s important to step back for a minute and acknowledge that the Commonwealth of Massachusetts at this time was one of the leaders in public education. So the fact that Munsell and Bradley and Prang were located in Massachusetts and this early excitement over color in art education took place in Boston was no surprise. Boston was a hotbed for this sort of thing.

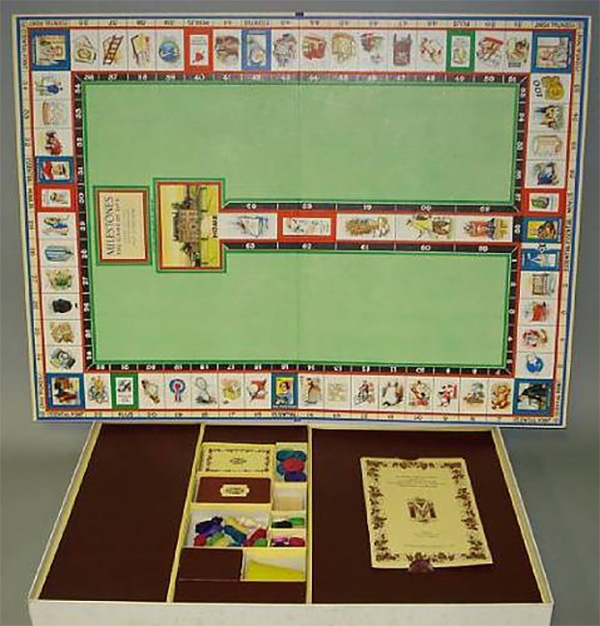

Milton Bradley we all recognize as the entrepreneur that invented the board game called “The Game of Life.” He took his fortune that he made from “LIFE” and reinvested his profits into developing kindergarten materials. He was inspired by Froebel, the founded of the kindergarten movement. By the 1880’s he was already creating color materials for the classroom.

Photo credit: Board Game Geek

Prang came from a slightly different background; he was probably the most famous chromolithographer in America. He was an immigrant from central Europe who had started a chromolithography business in Boston in the mid 1800’s. He printed things like trade cards, the little giveaway cards that you got when you went into a store. These polychrome printed cards often had humorous or sentimental pictures on them. People collected trade cards and put them in scrapbooks, much like people collect digital images and post them on Instagram today. He also printed decorative pictures for the home. He got into art education because he married a widow named Mary Dana Hicks who was a prominent art educator.

Munsell of course was coming from a completely different angle. He was not an entrepreneur or a skilled printer; he was a painter and an art educator. So when he entered the field of art education materials, he was up against these two very experienced businessmen. Both of them had one hand in the art education pie. Munsell faced great challenges.

Munsell was driven to “improve American public taste.” What did that mean for him and how did it effect his work?

One of Munsell’s pet peeves was popular taste – he was what we would refer to today as “a tastemaker.” He had an ideological agenda; his ambition was to improve public taste. He was horrified by all the brightly colored, sharply contrasting billboards, advertisements and ladies’ costumes that seemed to proliferate in the late 19th and early 20th century with the development of synthetic dyes and paints and pigments. His agenda was to get children to learn to appreciate tasteful colors at an early age. His system focused on popularizing subtle colors. As the book explains, it is very difficult for children to actually see subtle colors. One reason why Milton Bradley and Louis Prang were more successful was because they understand this fundamental issue with children and color perception. So in addition to the problem of Munsell not being able to get the chromolithographers to work with him, he was somewhat limited by his ambition as a tastemaker.

In Part 2 of our series, we talk with Regina about the auto industry, the World’s Fair of 1933, and Munsell’s “eureka” moment.

About the Author

Regina Lee Blaszczyk is the Leadership Chair in the History of Business and Society at the University of Leeds. Her career has included jobs as a cultural history curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington, DC; as an American studies professor at Boston University; and as program director at the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia. She is an associate editor at the Journal of Design History, the top design history journal for the humanities. She also serves on the editorial boards of Enterprise and Society and History of Retailing and Consumption. She has written many books and articles on the cultural history of business with reference to design, fashion, color, retailing and advertising, including The Color Revolution.

Leave a Reply