In the final chapter of our series on The Color Revolution, we talk with author Regina Lee Blaszczyk about the importance of color theory, color trends and what Munsell would think about our color world today.

Do you think the speed of color trends is going to continue to increase?

As a historian, I’m not the best person to ask about contemporary practice. However, I can say something about historical trends and their influence. I have a new project called The Enterprise of Culture, which deals with the business history of fashion in Europe and America after World War II. If history tells us anything about changing color trends for fashion, we are always going to be limited by the seasons. The fashion business, which sets many color trends today, has seasonal shows and those seasonal shows occur on a regular basis. New colors, which are coordinated across industries, are actually tied into those seasonal shows. Unless we introduce more seasons in the fashion palette, I don’t think there’s going to be much change. I think that the system that was in place in the days of Margaret Hayden Rorke, who was the managing director of the Color Association of the United States from the 1910s to the 1950s, is similar to the cycle that you see today.

Do you think the speed could lead to more consolidation or will the pendulum swing?

People often asked me when I was writing this book, “Is green going to be the only color that’s going to be available because Pantone said emerald green is the new ‘it’ color for 2013?” The answer is “No that is not going to happen.” We live in a different world than our Victorian ancestors. When mauve mania swept across England, France, and the United States back in the 1860’s, ladies had very few clothes. If you had a mauve dress, that mauve dress would be your fashion statement for that year, and for the next year, and the year after, and the year after that. Today we can go shopping at fast fashion outlets like Zara, H&M, and Primark and get a whole new wardrobe for less than it would have cost to have a dressmaker sew up that one mauve dress. The circumstances are completely different today. In the time of mauve mania, people didn’t wear clothes a few times and then get rid of them. You didn’t have “fast fashion” or disposable clothing in the 1860’s and 1870‘s.

A dress displayed in London’s Crystal Palace exhibition of 1862. The fabric was colored mauve by aniline dyes made by G.F. Perkin and Sons. Science Museum/SSPL, London.

In the book you mention attending a Color Marketing Group event, what was the most inspirational thing you learned?

When I started working on this book, I was a professor at Boston University and had a sabbatical year at Harvard. In Boston that year the Color Marketing Group had one of their semi-annual meetings. Working through the CMG’s publicist, I was given the privilege of sitting in on the meeting, which dealt with color predictions for the hospitality and home-furnishings fields. It was a very illuminating experience for me.

The meeting consisted of a serious of concurrent seminars where groups of 15 to 20 people sat around a table and discussed contemporary culture. I went to one of the sessions on technology and color, sitting side-by-side with color professionals from Fortune 500 companies and other global corporations who were talking about the impact of technology on the color palette. I went to other sessions where people were discussing other popular themes and how they would have an impact on the color palette. The discussions were very sophisticated, much like a graduate seminar in sociology or anthropology. I was impressed by how much of what was being discussed was based on a combination of experience and intuition.

I was not able to sit in on the final session where the Color Marketing Group decided on the color palette for the upcoming season. That session was confidential, understandably. But I was free to wander around as I pleased and to sit in on many sessions and was struck by how similar their modus operandi was to that of Towle, or Ketcham, or another important midcentury colorist, Faber Birren. Even though the time was different, the place was different, and the products were different, the process of color selection was really the same. The professional colorists of the color revolution had laid the foundation.

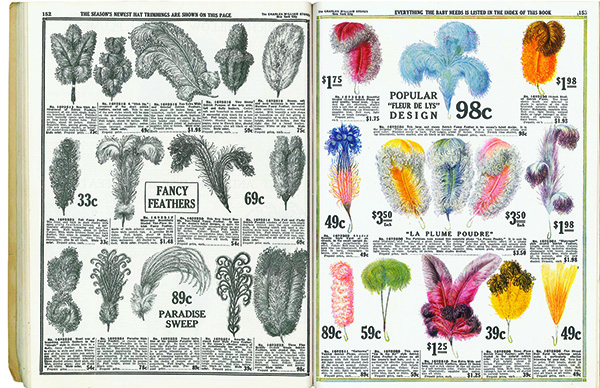

Advertisement for dyed ostrich feathers, used to add style to ladies’ hats. From New York Styles, Spring and Summer 1914 (Charles Williams Stores, 1914).

What about the importance of color theory?

I think that Munsell would be happy to see that color theory is an important part of the curriculum in American art schools and art programs today. I think that he would like to see more of an emphasis on good taste and perhaps on the scientific selection of colors.

When I was an art student many years ago, we used the work of Josef Albers to study color. Josef Albers was an immigrant who had worked at the Bauhaus in Germany and brought Bauhaus traditions with him to the United States in the late 1930’s. He taught initially at Black Mountain College and then at Yale University. In the 1960’s he published an important oversized folio called Interaction of Color, which went into a paperback edition that was widely used in art courses from the 1970’s onward. Albers was different than Munsell in that Albers felt that color was something that could not be systematized, and that color perception was based very much on the individual. By studying the juxtaposition of different hues and different color swatches, the individual designer, artist or consumer could come to his or her own conclusions about which colors looked good together or which color effects could be achieved. By contrast, Albert Munsell was a systematizer who believed that you could create rules, and that rules could be followed in order to understand color harmony. Albers didn’t care about color harmony; he cared about color expression.

Munsell cared about color harmony and good taste. By the late 20th century, color theory was widely taught in art schools in a very different way than Albert Munsell had envisioned. I think that he would be pleased on the one hand, but then he would be somewhat frustrated on the other.

Is color theory more integrated in terms of letting people choose from all the systems we have available today?

I think the Bauhaus method, which is much more about personal expression, is more prominent than the Munsell system in art schools today. When I was writing this book I got a few standard questions: Is there a color conspiracy? Why can’t I find a yellow sweater this year? Are you writing about Josef Albers? These were some of the 4 or 5 questions that came up. Albers was always one of them, not Munsell. So I think that the Albers technique of the “interaction of color” is still very prominent in the United States. People who grew up in the late 20th century and who became art students learned Albers and not Munsell. A far as I could tell, when I was writing the book, Munsell was very heavily used in the sciences and less so in art.

There are many colors systems and there’s no best way. It’s really up to the individual to find a system or combination of systems that suit their work and their market.

What do you think Albert Munsell would think of our color world today?

Our color world? I think Albert would be appalled by the bling. As I mentioned, he was a tastemaker and he felt that the bright new colors that were created by the synthetic dyes and pigments were not in good taste. He wanted to see subtle hues that had grey in them; he appreciated subdued colors. If he looked at the screen of an Apple computer, I think that he would find the color to be rather garish and somewhat like the palettes presented by his rivals Milton Bradley and Louis Prang.

Advertisement for paint, Literary Digest, Feb. 11, 1928

At end of book you say, we are “unmindful of its wonders.” It being color. What do you wish people would see or pay attention to?

I think people are generally unaware of the material world. We live in a material world and we “shop ‘til we drop,” but I think people are generally unreflective about their surroundings. This is an issue I have discussed with some of my colleagues in design history and with my students in the School of History at the University of Leeds in England. People are generally unaware and incurious about their surroundings and how their surroundings came to look the way they do. I’m the sort of person who, when walking down the street, looks at the architecture and asks: “When was that building built?” or “Was that building altered after it was built?” I think that many people are not that cognizant of the material world. I think we would generally be more appreciative of our possessions and perhaps less wasteful as consumers if we became more aware of the work that went into creating and designing objects. I think this is something Munsell would have appreciated as well. In other words, if we learned more about the material world and its history, we would have more of a “treasure chest” approach to our possessions and less of a “throwaway” approach. I have written about this idea in another book, American Consumer Society, 1865-2005: From Hearth to HDTV.

What also strikes me is the lack of understanding amongst designers and marketers about the history of design and marketing and color. I hope that The Color Revolution book suggests to designers and marketers that there’s a very rich story of how color was used historically. There’s a rich story to design that goes beyond the celebrity designers and genius designers and their genius creations. I also think historians have lost the storytelling part of their jobs. So often, you read history books and they’re highly specialized monographs written for other historians. I like to write history books that are well-researched, but that any educated, curious adult could read. I hope to reach the nonacademic reader who might find ideas that relate to the work they do.

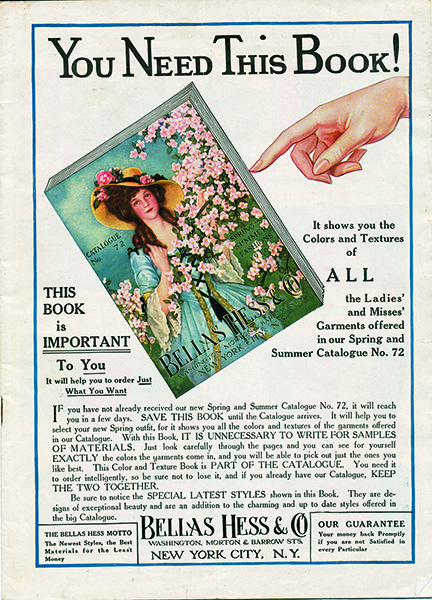

This 1916 catalog supplement contained swatches in the pale wartime hues as an aid to color selection.

I don’t write about famous people like Karl Lagerfeld. I write about the people who work for him. It seems much more interesting to me and much more informative to read about someone like Towle or Rorke, who have been forgotten by history, but who helped to create the invisible technologies that Edgerton reminds us are very important. I call these people “fashion intermediaries.” They are the people who work behind the scenes in design and fashion to make the material world that we live in today. They work as retail buyers, store designers, window dressers. They work as colorists. These are the people in design and marketing history that get overlooked. Their stories need to be told.

About the Author

Regina Lee Blaszczyk is the Leadership Chair in the History of Business and Society at the University of Leeds. Her career has included jobs as a cultural history curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington, DC; as an American studies professor at Boston University; and as program director at the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia. She is an associate editor at the Journal of Design History, the top design history journal for the humanities. She also serves on the editorial boards of Enterprise and Society and History of Retailing and Consumption. She has written many books and articles on the cultural history of business with reference to design, fashion, color, retailing and advertising, including The Color Revolution.

Leave a Reply