In Part 2 of our series, we continue our conversation with The Color Revolution author, Regina Lee Blaszczyk, discussing the auto industry, the World’s Fair of 1933 and Munsell’s “eureka” moment.

Can you talk about Munsell’s “eureka” moment?

In August of 1893, Munsell was on holiday in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and he saw thunder clouds roll in while he was sketching. He liked to go sketching on one of the islands near Portsmouth. It was a favorite place for artists to work because it had peculiar weather conditions that created very dramatic skyscapes – the island was called “Smutty Nose.” The weather changed very quickly, and Munsell made a watercolor sketch called “War Cloud.” I haven’t been able to find this sketch–it has not survived in any collections that are available to researchers. Munsell tried to capture the subtle colors of this furious sky in his sketch. As he was doing this sketch, he had one of those “eureka” moments that are famous in the history of invention. Munsell’s notes from the time suggest that he thought something like: “I’m going to go back to my studio in Boston and I am going to plot on a sphere these color gradations that I see in the sky. I will able to use this color sphere as an object lesson to teach my students the principles of color harmony.” So this led to the invention of the Munsell color sphere which was patented in 1900. This moment in 1898 was important because it crystallized ideas that were already developing within Munsell from his days as a student in Paris and his days as a young instructor at the Massachusetts College of Art; it really led to his pushing ahead with his life’s work in color invention and innovation.

Color management became an important tool during the 1920’s. How did Munsell play a role?

Munsell died in 1918. One of his sons took over the business, created the Munsell Color Foundation, and moved the whole process out of art education and into the sciences. It was through this educational foundation that the Munsell Color System finally gained some traction and the attention of the U.S. Bureau of Standards. By 1923, Munsell crayons were being manufactured. I was much more interested in the art implications than the scientific, so I didn’t discuss the subsequent history of Munsell in the sciences because, that’s a different story.

Tell us about H. Ledyard Towle & Howard Ketcham in relation to the Munsell system

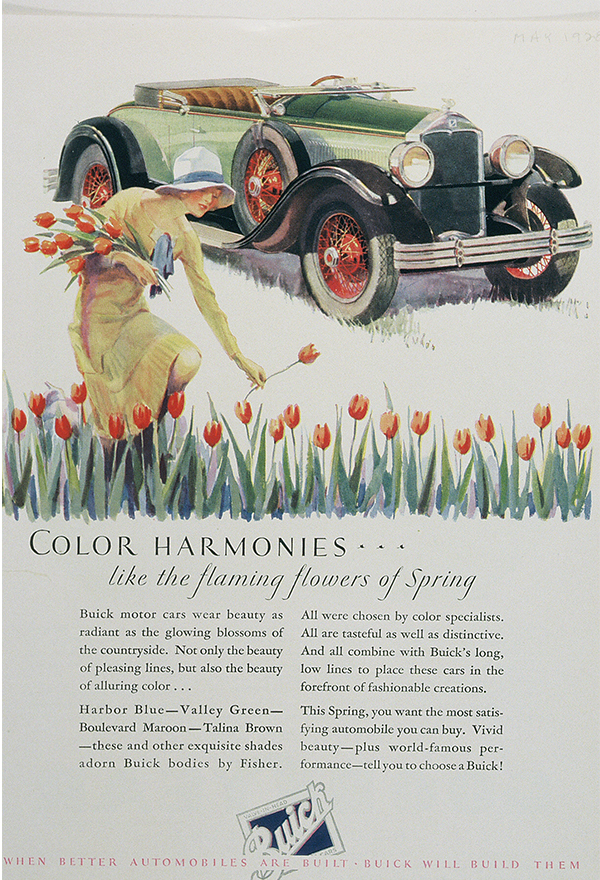

In the 1920s, the DuPont Company hired Towle to establish the Duco Color Advisory service and to design color combinations for the auto industry. Towle was trained as an artist, was a camouflage expert during World War I, and had worked on Madison Avenue as a “Mad Man” before going to DuPont to help them manage all of the new lacquer colors they had developed for Detroit. Towle rejected the Munsell system, saying it was too rigid and stifled creativity. Howard Ketcham, Towle’s successor at DuPont, came back to the system to help simplify a color palette that had gotten out of control, establishing standards for the auto industry.

This story shows you that color systems are really up for grabs. There are many systems and you can use them or you can decide not to use them. I think there is a myth in American popular culture that there is a “color conspiracy,” that there is one color system that everyone follows. There really isn’t, there are many systems with different applications that people use in different ways. I think the example of Towle rejecting the Munsell system and Ketcham accepting it, really demonstrates this point quite nicely.

World’s fairs were used as a testing grounds for “evolving theories about color and electric lighting, color and sound, and color and mood.” Is this still true today? Is there some other venue that plays a similar role?

The Century of Progress Exposition was not the first world’s fair to use color, but it was probably the most important world’s fair to use color as a motif. World’s fairs were introduced in 1851 in London, when the Crystal Palace exhibition put the arts and industries of all nations on display. From the 1850’s through today, the world’s fairs bring together the best manufactured products from all over the world and put them on display for the public to see.

In the 1850’s, 1930’s and even in the 1960’s, world’s fairs were much more important than they are today. People didn’t have TV, radio, the Internet or shopping malls. The fairs were places for people to go in the summer to be entertained and to educate themselves on the newest products. After the introduction of electricity in the 1880’s, you see a greater use of light and color as decorative motifs in the world’s fairs. This begins in Paris in 1889 when the Eiffel Tower was constructed and lit up. It continues at the Chicago world’s fair in 1893. This fair was called the “white city” because the fairgrounds and buildings were lit up with so many white lights. The Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco in the first decade of the 20th century introduced the combination of electric lights and polychrome color. By the time you get to 1933 and the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago, you see a full-scale celebration of electric light and color.

How was the 1933 World’s Fair a “marriage of art and science?”

What’s distinctive about the 1933 world’s fair is that the exteriors of all the building were painted in extremely bright, carnivalesque color schemes that were designed, in part, by the architect Joseph Urban. I called it a “marriage of art and science” because in this colorscape you see an architect and his team collaborating with electrical engineers from some of the leading companies.

Munsell often met with, collaborated with, and talked with color scientists from MIT and other universities. He longed to be able to create a color system that would be useful to artists and respected by scientists. The desire to merge art and science was one of his struggles. With the 1933 Chicago world’s fair, you begin to see the interdisciplinary collaboration that Munsell longed to achieve, in the collaboration between architects and engineers.

It must have been a very visually exciting time for people, with the discovery of all these new colors.

I think that today we’re so accustomed to sitting in front of computer screens that have made brilliant color an immediate and commonplace experience. I’m sitting in front of my iMac, and it has the ability to produce an incredible number of colors. Our mobile phones have sharp beautiful screens that give us bright colors. We take it for granted that manmade color is available and part of our daily lives. But back in the late 19th and early 20th century, this was not the case. For example, the colors on your phone don’t fade, they are going to be colorful and luminous as long as you have that phone. Back in the 18th century, people also had bright colors, but those bright colors were somewhat rare and they were not permanent. For example, purple and mauve were available colors in the 18th century, but it was extremely difficult to create those colors. Purple became the color for royalty because it was so expensive to obtain the dyes to create purple textiles.

One of the reasons why we had a color revolution in the United States in the 1920’s was because of the maturation of the American chemical industry. Previous to that, the German dye industry had dominated the world and introduced many important hues and permanent dyes. However, during World War I, supplies of German dyes to America were blocked, and the American chemical industry took off. Companies like DuPont began to experiment, not only with dyes for clothing, but with creating a whole range of other types of colorants. For the first time, you had mass-market cars available in bright colors. Rich people always had brightly colored cars because they could have them painted and repainted with carriage paints, but the car for the ordinary person in bright, durable colors was not really available until the 1920’s. What you see in the 1920’s is this startling new world of bright, durable color.

If you’ve ever wandered around and looked at skyscrapers from the 1910’s, the 1920’s and the 1930’s, they have bright terracotta ornamentation on them. There are a couple of really prominent ones like the Woolworth Building from 1913, decorated with terracotta ornaments and lit up with colored lights. The Woolworth Building had polychrome effects much like the Empire State Building, built in 1931. The tradition of lighting up buildings in bright hues was part of the color revolution. So beginning in the 1920’s you have a widespread use of color in architecture, design, and illumination. This was an important step in the color revolution.

In Part 3 of our series, we talk with Regina about the early color swatch books, color standards and the influence of color.

About the Author

Regina Lee Blaszczyk is the Leadership Chair in the History of Business and Society at the University of Leeds. Her career has included jobs as a cultural history curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington, DC; as an American studies professor at Boston University; and as program director at the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia. She is an associate editor at the Journal of Design History, the top design history journal for the humanities. She also serves on the editorial boards of Enterprise and Society and History of Retailing and Consumption. She has written many books and articles on the cultural history of business with reference to design, fashion, color, retailing and advertising, including The Color Revolution.

Leave a Reply